ESPINAR

The postponed health of the conflict

In December, the Health Plan involving 180 rural villagers exposed to heavy metals in Espinar, Cusco, should have come to fruition, but they’re still waiting. The first 71 severe cases hadn’t received the specialized treatment that the Regulations demanded. The villagers complained to the Director of the Espinar Hospital, while the Deputy Minister of Health admitted the lack of coordination between the Cusco‘s officers.

Publicado: 24/12/2015

Actualizado: 15/02/2018

Contaminated Villagers On The Waiting List

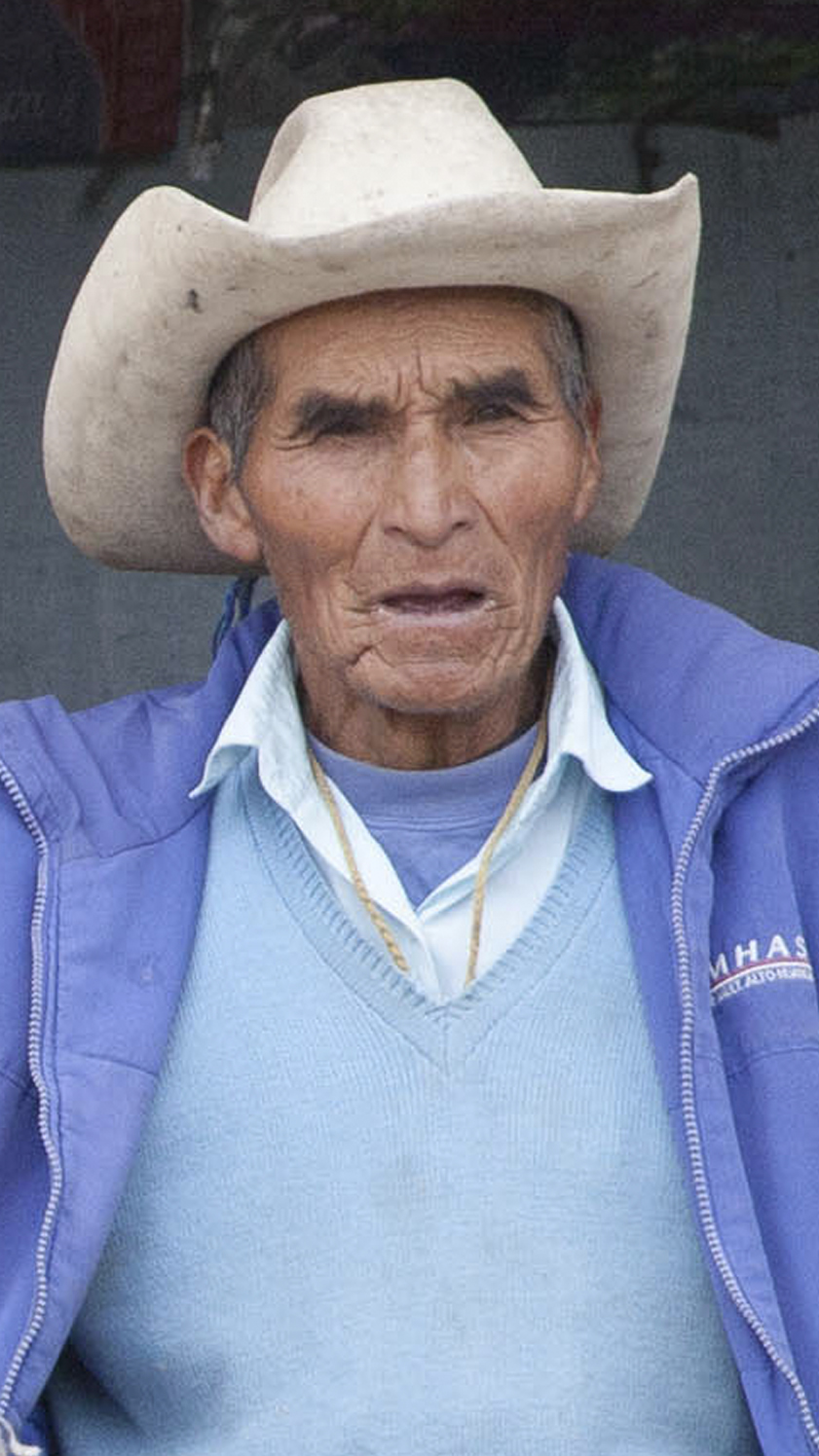

– -Do you have the list? We come from Alto Huacané-says Santusa Noñoncca to the young woman from the Sistema Integral de Salud (SIS) [Comprehensive Health System], who looks at her from the corner of her eye and answers: “Come back tomorrow. We’re not attending today”.

October 19th, 2 pm. Santusa is not alone. She had arrived at the Espinar Hospital, Cusco, with agroup of rural villagers to demand medical care. They are part of the 180 villagers from Alto Huancané and Huisa exposed to heavy metals, according to a 2013 study carried out by the Centro Nacional de Salud Ocupacional y Protección del Ambiente para la Salud (Censopas) [National Centre of Occupational Health and Environment Protection for Health], This study was commissioned by the round-table discussions established by the Government as an answer to the social conflicts triggered by protests against the ex-mining company Xstrata-Tintaya, currently managed by Glencore.

The villagers that arrived at the hospital live around 300 -1,000 feet from the mining residue deposits. They have lead, arsenic, mercury and cadmium in their bodies, all of them considered highly carcinogenic elements, among other 13 minerals. In some cases, the villagers’ exposition to toxic elements exceeds the World Health Organization parameters, as Convoca.pe verified in the first part of this investigation. What Santusa demanded that particular day was the list of villagers that were to be attended as a part of the Health Action Plan made for Espinar that the Ministry of Health approved in March of this year via the 205-2015/MINSA ministerial resolution.

Convoca.pe and La República newspaper joined Santusa and the other villagers in their visit to Espinar Hospital to check if the Health Plan was being executed. However, this team found that the 180 affected villagers hadn’t received neither specialized healthcare nor medical treatment for heavy metal exposition, even though the deadline was last December.

“The villagers that arrived at the hospital live around 300 -1000 feet away from the mining residue deposits. They have lead, arsenic, mercury and cadmium in their bodies, all of them considered highly carcinogenic elements”.

Neither Santusa nor the other villagers were attended to that afternoon at the Espinar Hospital, where a medical team arrived from Lima for a health campaign. The medical attention was focused on patients from the city, although the plan should focus on “specialized integrated medical attention to the eight communities located in the area of influence of the Xstrata Tintaya Company’s mining activities”.

Chronic cases

Over the following weeks, 71 out of 180 villagers considered to be “chronically exposed to heavy metals population” and had to receive healthcare at the end of May at latest, hadn’t received it yet. Medical attention for the other 109 and healthcare for the affected people should end this month. However, the first group appointments made for December 15th were cancelled, as Lolo Santillán, the Espinar Hospital Director confirmed. “We don’t have a new appointment” says Juan Magaño, President of the Huisa community.

To receive free healthcare, the Espinar Hopital demands the villagers to be affiliated to the SIS and show a document that proves their transference through a written report from a doctor of the nearest rural health clinic to their villages. Otherwise, they have to pay for the medical attention, as it happened to Melchora Surco Rimachi, president of the Alto Huancané community. She paid for her medical appointment, her 10 year old grandson, Yedamel’s and her 83 years old mother, Toribia Rimachi Ayma’s as well, as can be seen from the receipts dated October 23rd. They all have 17 heavy metals in their bodies.

“Public Health Deputy Minister, Percy Minaya, has promised to make every effort to guarantee the first 71 chronic cases will receive appropriated healthcare”.

Convoca.pe had access to Melchora’s family official results. Yedamel presents an excess of six outof eleven metals, while Melchora and Toribia have an excess of five out of eleven. The little boy’s exposition level to molybdenum is more than 3500% considering the parameters used by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), where the villagers’ urine samples were send by Censopas in 2013. Melchora’s and Toribia’s molybdenum limits were also greatly exceeded. Their house is located less than 700 feet from the Xstrata Tintaya’s Camaccmanyo tailing.

On October 23rd, Melchora handed the Espinar Hospital Director the list with the affected villagers from her community. Some of them received free healthcare only after complying with all the requirements, but they assure they have not received specialized healthcare yet. Most of the non-affiliated-to-SIS-villagers gave it up because of their financial situation and not being fully convinced that they would receive a successful treatment. Melchora made the first payments to get medical care for her family and herself, but after realizing how much she should pay at the end, she gave it up to, despite the fears. After Margarita Ccahuana’s death by chronic intoxication by cadmium and arsenic, the fears of the villagers have increased. In Huisa, there are at least other two similar cases reported.

“How long are we going to wait?” asks Melchora. Percy Minaya León, Public Health Deputy Minister, admitted to Convoca.pe on last Friday that the 13,000 medical appointments in Espinar that he made reference in the media in response to the first part of this investigation, does not necessarily include the 180 villagers of the plan. Minaya explained that one of the reasons is the villagers “have the idea that the exams we provide are not the “solution” to the problem”. He also admitted he did not know about the requirement of being affiliated to SIS to receive healthcare. “There is a problem in the interaction between the regional and the national activities”, but he promised to “take action to give the first 71 chronic cases appropriated healthcare”.

Toxic source

The first step of the treatment for the population exposed to heavy metals is the identification of the pollution source” claim Toxicologist Raúl Loayza from the Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia and former Health Minister, Óscar Ugarte. The same claim can be found in the Ministry of Health Clinic practices guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of intoxication by arsenic and lead.

“The accumulated exposition could have produced irreversible effects (…) what can be made now for the people, is to give them treatment” explains Ugarte, who was minister when the first Censopas study was carried out, in 2010.

“The accumulated exposition could have produced irreversible effects (…) what can be made now for the people, is to give them a treatment”

Oscar Ugarte, former Health Minister when thefirst Censopas study was carried out (2010)

The political answer to this medical issue was the instauration of round table discussions on July, 2013. However, former Health Minister Alberto Tejada considered that “the health issue was not the most relevant in the negotiation table. Everything was about the environmental agenda”. On the “Integrated Final Report of Participative Environmental Health Monitoring”, the round table discussion final conclusion, the contamination sources were not determined in a conclusive way, even though the technical institutions involved in the problem participated on the negotiations: the Ministry of the Environment, the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Energy, Mining and Agriculture.

This absence has allowed the Antapaccay Mining Company, which is in charge of Xstrata Tintaya from May, 2013 to declare: “We do not accept any liability about the Espinar pollution” (See Box). However, the Camaccmayo ravine’s and the Tintaya River’s micro-basins that flow into the Salado river (water source for the villager’s livestock) “are born in the Tintaya’s property” affirms the Water Balance Final Report from January, 2014 prepared by the National Water Authority .

The round table discussion final report mentions that on January 10th and 11th, there was a special supervision to Tintaya’s operations and “Leakages from the Camaccmayo’s tailings press into the natural soil” were observed. The Agency for Assessment and Environmental Control (Organismo de Evaluación y Fiscalización Ambiental - OEFA) started a sanction process to the Company because of this infraction. Also, “Metal concentrations on sediments that exceeded the Canada’s Intermediate Standard of Sediment Quality established values” were found on three ravines, Tintaya among them, with concentrations of arsenic, cadmium and lead.

The reports about dead cattle in the communities did not get much attention in the round table discussion either. In the final report of the Environmental Health Monitoring, an analysis from the Agricultural Health Service was considered, were 27 samples from nine dead animals were tested and it was concluded that the cattle presented cadmium and lead levels “below the minimal lethal doses”. Nevertheless, the same study assures the number analyzed does not constitutes a “representative study of the evaluated area”.

Leakages in the Paccpaco zone in the AltoHuancané community affects the cattle. Picture by Miguel Mejía – La República.

Only this July 30th, the Agency for Assessment and Environmental Control (OEFA) approved the Peruvian Nuclear Energy Institute request to investigate where the contamination comes from.

Revolving doors

The postergations made to Espinar have happened at the same time as the cases of conflicts of interest. The most relevant is the case of Elvis Medina Peralta, former Tintaya’s Environmental Superintendent between May 2006 and April 2013 (the round table discussion’s time lapse) and General Director of Environmental Affairs of Minem since last March, when he approved the Company’s environmental assessments.

He is not they only case. Between 2002 and 2006, Carlos Loret de Mola was the Director of the Minam’s predecessor, the National Environment Council, and at the same time, he was Director of Fundación Tintaya (Tintaya Foundation). As the Foundation’s director, on August 16th, 2012 he signed one of the Espinar’s round table discussions acts. However, Loret de Mola claimed to Convoca.pethat he worked in the company ad honorem. When he left his position, he was hired again by the State as the responsible of the Public Front for the World Conference on Climate Change (COP20) held one year ago in Lima.

“Espinar is a representative case of rights violations that authorities don’t deal with it, despite the evidences and conflicts of interests” says lawyer Juan Carlos Ruiz from the Instituto de Defensa Legal (Institute of Legal Defense), who besides CooperAcción and Human Rights Without Borders filed a lawsuit to make the State to prioritize the health of the people.

- 71people

were considered

to be severe exposed

to heavy metals - There only

300 ft between the tailings

and some of the houses

The authorities of Justice know very well what happens here. Former provincial Criminal Prosecutor of Espinar, Andronika Zans Rivera, asked the Public Ministry in March, 2014 for fresh water bottles for her personnel, as the water from Espinar “was contaminated by the several exploiting mining companies” (as she notified it). Five years after the first medical evidences were known, the affected villagers are still on the waiting list for the same demand.

Voices of Espinar

Villagers from the Espinar communities tell us how they feel affected by the heavy metals exposition. There is also a meeting of the villagers representatives and the Director of the Espinar Hospital, who demanded as a condition to be attended for free to be affiliated to SIS and have a written report from their village’s doctor (Click in each picture to watch the video).

Mining company insists the contamination is from a natural source

Antapaccay Mining Company, that belongs to Glencore and operates now in Espinar, gave us their version via email. It claims that “The very few heavy metals present in the water […] have a natural and geological origin”.

The also assure that “the 98% of the heavy metals and other elements evaluated (as a part of the Final Environmental Participative Monitoring Report for Espinar) on the sampled waters […] indicate that there is no contamination related to the mining activities, because they comply with the Environmental Quality Standards.”

Antapaccay fails to mention the controversial points of the round table discussions final report described in this article. “We do not accept liabilities, and the studies carried out by competent organisms and the participation of the civil organized society support us. Currently, the competent organisms are carrying out supplementary studies to determine the incidence. We are waiting for these results.” they conclude.

Comentarios

CREDITS

Edition: Milagros Salazar. Research: Gabriel Arriarán and Milagros Salazar. Translated by: Andrea Duffau. Video and audio editing: Stefany Aquise. Photographs: Miguel Mejía (La República) and Milagros Salazar. Web development: Interself.pe. Map: Víctor Anaya. Revieweb by:Louella Mahabir. Coordination: Juan Arellano for Traduciendo América Latina, a project of Global Voices in Spanish.

![Faustina Ñoñoncca went to the Espinar Hospital along with other Huisa’s villagers, but thewoman in charge of the Sistema Integral de Salud (SIS) [Comprehensive Health System], didn’t receive her that day (October 19th). Picture by Miguel Mejía Castro -La República.](imagenes/galeria/parte2/8.jpg)